OTA Value: It Depends on How You Play the Game!

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Many hospitality owners and consultants hold a short run view that OTA’s are overly powerful market actors, who use their sizeable marketing budgets, expansive consumer reach and, increasingly, their reward/loyalty programs, to force rate discounting; collect unreasonable fees; and interpose themselves in the guest-and-lodging service provider relationships.

There is an alternate long run point of view:

- Ultimately, the market forces of supply and demand determine price. Asset owners have the power to control room inventory supply versus demand. When room supply is effectively matched with demand, a major short run incentive to discount rates is removed.

- Asset managers can and should focus primarily on creating value for their guests; giving new guests delivered by OTAs reasons to choose their properties – and book direct – in the future; incenting loyal guests to return again and again; and encouraging guest-advocates to communicate why they value their properties. This produces a sustained core of room demand (and occupancy) and reduces the need to rate discount as a way to sustain occupancy.

- OTA senior management should take a long term partnership approach with hospitality suppliers focusing on value creation and promotion for both the customer and the supplier.

- It is in the OTAs’ long run interest to deliver more personalized, targeted recommendations to consumers based on what they know about them and the properties that choose to be listed. Choice displays, particularly default sorts, should be based primarily on projected guest lodging service value – price and service and less on payment by suppliers.

- OTAs create value for suppliers by producing incremental customers (e.g., non-loyal ones) that those suppliers are not likely, or less expensively able, to get on their own. OTAs need to more effectively demonstrate and align distribution versus media marketing costs to hotels.

There can and should be a common long run ground for hotels and OTAs

Read the Full Article below:

“Many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our point of view.” Obi Wan Kenobi, Return of the Jedi, Star Wars Movie Series

Debate over the value of online travel agents (OTAs) and their impact on ADR and profitability for hospitality owners and managers seems endless. The point of view for those debates may have a lot to do with this.

Many hospitality owners and managers (plus some consultants and vendors) hold a short run view that OTAs (and their meta-search counterparts and subsidiaries) are overly powerful market actors. They use their sizable marketing budgets, expansive consumer reach and, increasingly, their reward/loyalty programs, to force rate discounting; collect unreasonable fees (or merchant margins – a markup of hotel provided rate retained by the OTA a time of sale); and interpose themselves in the guest-and-lodging service provider relationships (e.g., loyalty).

There is an alternate point of view. Long run lodging financial sustainability can, and often is, undermined by short run price discounting. This occurs when lodging supply exceeds demand and is exacerbated by OTA over-reliance on price as the prime (default) sort determinant in their website displays. In the long run, solutions to this problem are in the hands of hospitality managers and owners and OTA senior management. Consider a long run market point of view:

- Ultimately, the market forces of supply and demand determine price. Asset owners have the power to control room inventory supply versus demand. This includes accurate forecasting of room demand versus supply plus consideration of rooms supply via the share economy (i.e., Airbnb, Home Away, etc.). When room supply is effectively matched with demand, a major short run incentive to discount rates is removed.

- Asset managers can and should focus primarily on creating value for their guests; give new guests (including those delivered by OTAs) reasons to choose their properties or chains in the future; incent loyal (satisfied) guests to return again and again; and encourage guest-advocates to communicate why they value their properties. This produces a sustained core of room demand (and occupancy) and reduces the need to rate discount as a way to sustain occupancy. Management focus should be on the size and sustainability of this core over time with OTAs as means to augment the core and less on the percentage mix of OTA bookings.[i]

- OTA senior management can, and in some cases does, take a long term partnership approach with owners and managers (i.e., a case in point is the well be the publicized relationships between Expedia and Marriott announced September 16, 2016). Such relationships can focus on value creation and promotion for both the customer and the supplier.

- Value for the consumer is created through OTA choice displays (e.g., via sort options and default sorts of hotel listings) based on both price and projected guest lodging service value for the consumer from participating properties. It is in the OTAs’ long run interest to deliver more personalized (i.e., targeted) recommendations to consumers based on what they know about them and the properties that choose to be listed.

- OTAs create value for suppliers by producing incremental customers (e.g., non-loyal ones) that those suppliers are not likely, or less expensively able, to get on their own. This can be done by serving as both a distribution channel and marketing media for hotels. As OTAs more effectively demonstrate and align distribution versus media marketing costs to hotels with the benefits, an improved long-term business partnership is more likely.

- For independent properties, determination of the benefits versus costs for OTA participation needs to be evaluated versus the costs of achieving similar benefits from chain membership with its attendant fees and costs.

Some Facts

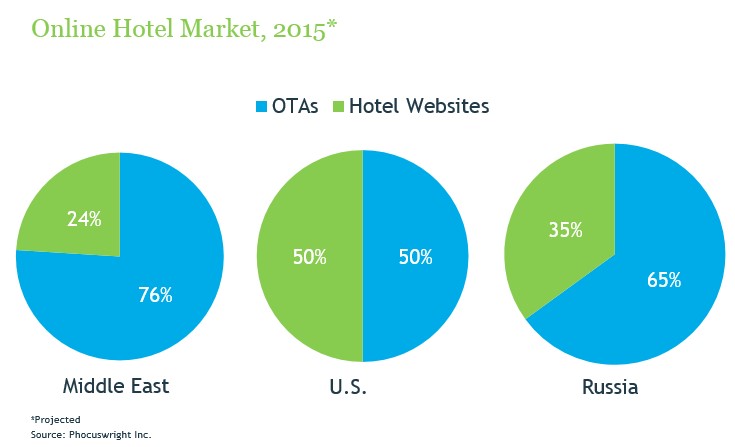

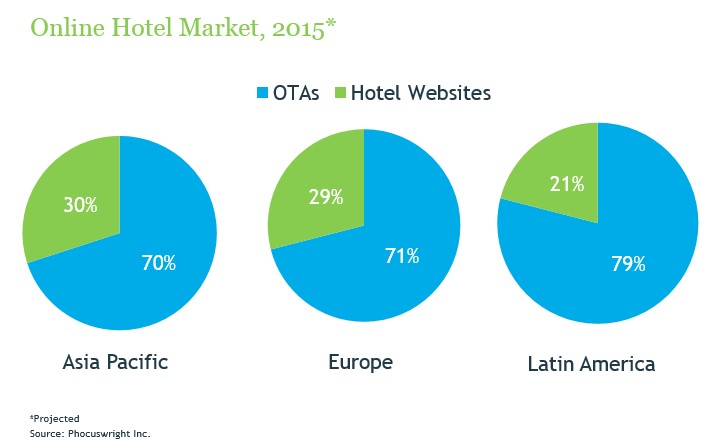

On a global scale, OTAs and their meta-search counterparts continue to capture an increasing share of online hotel bookings. See Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Hotel vs OTA Share of Online Hotel Revenue

This is despite significant efforts (and advice by some consultants) for chains and some properties to shift OTA bookings to hotel-direct channels.

It is interesting to note that in global regions where chain membership is low, OTA participation is higher. It may be that hotels see greater value in using OTAs (and other intermediary services) than incurring the cost of chain membership. An alternate point of view is that chain membership gives individual hotels greater leverage in OTA negotiations over fees.

In the US many chains have been focused on shifting the percent of bookings going to their direct distribution channels. While there has been some mix shift over the past decade, recent efforts have not produced a significant shift. See Figure 2.

Figure 2:

U.S. Percent Share of Online Hotel Revenue

2012 – 2017

| Year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Hotel Website | 54% | 51% | 50% | 50% | 49% | 49% |

| OTA Website | 46% | 49% | 50% | 50% | 51% | 51% |

Source: Phocuswright

- Note: US has the highest percent of chain hotels. Chains have been aggressive in trying to drive bookings to their properties’ websites. As shown in Figure 1, other regions have much lower penetration of chain membership and these (independent) properties are typically more reliant on the OTA channel for bookings. Also, the US data is consistent with the research done by Chris Anderson over the same time period, though it shows a much greater reliance by consumers on OTA displays for consumer choice.

Aggressive marketing efforts by chains and hotels to shift bookings to direct channels can be costly (facts about such costs are difficult to find). Moreover, OTAs like Expedia spend nearly half of their revenues on marketing and almost one-third on IT.[ii] This type of market power is difficult (and costly) for chains and hotels to match.

In some cases, chains and independents are trying to use their loyalty programs as an instrument to break OTA rate parity (an agreement between OTAs and properties that publically available rate levels offered to OTAs cannot be lower on hotel websites). When a hotel or chains offers a lower rate and additional benefits (i.e., for loyal customers), the likelihood for the booking to be made via a hotel-direct channel is enhanced.

While this approach may have some impact, OTAs have the ability to use their own loyalty programs and packaging to offer lower rates than those offered by participating hotels and provide rewards on all travel bookings, not just hotels. Moreover, many hotel guests belong to more than one hotel loyalty program, making them potentially less loyal to any one hotel or chain.

The important question for hotel owners and managers is whether investment, or perhaps worse, over-investment in loyalty program and direct-only booking campaigns are worth the return, particularly in the long run. This is the question that owners, managers and consultants should be asking! For independent properties, the question is even more complex, as owners must also evaluate the costs and benefits of chain membership. In addition, they have the option of joining (and paying for) membership in separate independent loyalty programs like Stash in the US, and purchasing separately many chain provided services from independent vendors.

Some Simple Economics

Numerous articles on market behavior by hotels in competitive sets suggest that price discounting leads to ever-falling prices, RevPAR and profits when there is excess room inventory in the market.[iii] Moreover, efforts to raise rates when there is excess room supply likely leads to falling revenue, RevPAR and profits.

When there is excess room inventory in the market, in general or seasonally, intermediaries can generate incremental demand for a given property or set of properties. They do this by shifting market share to select (by OTAs) properties and away from other properties within the competitive sets. It is unlikely, and to my knowledge has not been shown, that OTAs have had a significant effect on driving primary (i.e., non-share-shift) demand to a given competitive set in the aggregate. There is ample evidence that they can impact demand.[iv]

OTAs focused only on price discounting facilitate this market dynamic. That leads to falling ADR for all or most properties in a competitive set. Owners who expand supply in competitive sets or fail to consider the effects of share-economy room supply in development planning do as well.

There are ways for hotels owners and managers to reduce the effects of price competition (in general and through OTAs) and support efforts to raise prices within competitive sets, even in the short run. In summary, these include:

- Providing better service and facilities than the competition; growing the base of loyal and repeat guests; and creating guest-advocates for the property as part of an effective marketing and sales effort. In a phrase, do a better job than competition in service operations and marketing.

- Creating, maintaining and marketing a sufficiently differentiated service (e.g., preferred location, brand, etc.) for a sizeable enough target market to achieve profitable occupancy levels at prices above competitors.

- Managing prices in accordance with periods of excess demand via effective price management and/or revenue management. (NOTE: In periods of excess supply, hotels can resist to extent possible, given market forces, reducing prices or over-discounting relative to typical seasonal pricing patterns. This approach is difficult and requires a disciplined approach to pricing and marketing by asset managers.)

- Observing and responding appropriately to the pricing actions of price-leader properties within competitive sets.

- Being a responsible price leader within a competitive set: Consistently and systematically execute rate increase actions that competitors can observe publically. Match price increases by followers quickly and visibly. (NOTE: Price leader properties are typically ones that have achieved prominence in areas covered by points 1, 2 and 3 above.)

OTAs can have a role in helping properties with these activities. They are in a position to forecast aggregate lodging demand for competitive sets. They have visibility over factors effecting demand – demand for air travel, site user activity, traveler interest in given destinations, and so forth. They are also in a position to compare that data with other destinations and over time. In sum, OTAs have publically available data on travel and lodging demand and prices that individual properties and chains may not. They could and should share it.

OTAs are a repository of public future rate information within competitive sets. Many properties already make use of that information as part of their regular rate monitoring and management activities.[v] To the extent that OTAs typically drive less brand (property) loyal (i.e., mercenary) demand, they are in a position to evaluate for, and perhaps communicate to, all participating properties in a competitive set how much incremental demand can be shifted during excess supply periods. In a phrase, they can be source of mercenary consumer hotel price response values. (NOTE: The formal term used by economists for this is price elasticity of demand that measures in percentage terms the change in revenue with a given percentage change in price, when all other factors are held constant.)

OTAs can also help hotel managers and owners gauge the amount of share economy room supply in a given market. For example, Expedia lists Home Away inventory. As we will discuss below, this could be a valuable source of information relative to potential or actual share economy lodging supply for asset owners or investors.

Over the long run OTAs can become a repository and provider of information about user behavior, specifically more personalized behavior, relative to hotel choice on their websites. They are in a position to assist individual properties with effective representations and promotions of service values – brand promises, peer-evaluations and prices in OTA displays. They could do this in terms of both target markets and competitors.

A Possible End Result

If all of this sounds farfetched, consider the following.

As OTAs become more prominent marketing and distribution solution partners, merchant margins can be reduced and rationalized relative to their separate marketing and distribution values for hotels. In effect, OTAs can demonstrate the media value for hotels, perhaps as an extension of “billboard effect” research. Moreover, reduced merchant fee levels can be offset by fees for distribution and marketing services aligned with the value they deliver to owners. This can sustain long term market value and profits for both hotels and OTAs.

As owners restrict room supply versus demand more effectively, they can sustain ADR, occupancy and profit. Managers of individual properties can create and promote services that keep their guests coming back and telling others why they do. Their properties’ RevPARs, ADRs, occupancies and profits can increase and be sustained. And, as ADR rises, so does the absolute value of OTA merchant margins even if the percent margins do not. Finally, when the OTAs, managers and owners focus on growing total market and/or specific destination demand, long run profits for all can be sustained.

Perhaps the long run solution for OTAs and hotels is not a zero sum game. All can win if the game is played right

Footnote:

[i] One of Cayuga Consultants, Gordon Carncross has had a very successful practice helping hotels create and maintain their core business as a key pathway to long run financial success.

[ii] See SEC Filing 10K for Expedia, 2016.

[iii] See chapter 13 of Cornell on Hospitality, “Demand Management,” John Wiley and Sons, 2011.

[iv] See CK Anderson, “The Billboard Effect: Online Travel Agent Impact on Non-OTA Reservation Volume,” Cornell Center for Hospitality Research Report, 2009; CK Anderson, “Search, OTAs, and Online Booking: An Expanded Analysis of the Billboard Effect,” Cornell Center for Hospitality Research Report, 2011; …

[v] See for example, eRevMax and TravelClick

About the author

Bill Carroll is actively engaged with hotel ownership groups, intermediaries and start ups in the areas of digital media management, pricing, and marketing. He is capable of taking a holistic view of marketing, pricing, distribution and revenue management for hospitality related firms. He helps clients chart a successful courses of action through improved strategic focus, organizational change and systems solutions choices. Bill is a Consulting Member of Cayuga Hospitality Consultants and a senior analyst with Phocuswright.

Contact Us